Social Media - Reset

last update: 4 January 2023

Google search for history of social media in science pdf

I admit it, in the past I used Facebook quite a lot, and input a lot of "stuff" into LinkedIn, and I suppose all the data is still there. So my first question is can I remove all trace of that old "stuff", not because it is in any way compromising, but simply because it is useless, and I don't see why social media sites should keep useless information about me (or past versions of me).

But I want to start with the "simple" question, what is social media and when did it all start? Then move on to what are the problems with social media?

I will admit I also found it interesting to deviate somewhat and included a description of how social media works in the background to optimise "consumer engagement". I hate being considered just another "consumer" to be "optimised".

Finally, I have to ask the question, what social media should I adopt now, if any?

What is social media?

Wikipedia has a long article on social media, and it starts by tells us that…

Social media are interactive media technologies that facilitate the creation and sharing of information, ideas, interests, and other forms of expression through virtual communities and networks. While challenges to the definition of social media arise due to the variety of stand-alone and built-in social media services currently available, there are some common features:-

Social media are interactive Web 2.0 Internet-based applications.

User-generated content, such as text posts or comments, digital photos or videos, and data generated through all online interactions, is the lifeblood of social media.

Users create service-specific profiles for the website or app that are designed and maintained by the social media organisation.

Social media helps the development of online social networks by connecting a user's profile with those of other individuals or groups.

Wikipedia places the history of social media in the domain of early computing, and more specifically in 1960 with the PLATO system, on which early examples of social media applications were developed, e.g. forums (message boards), e-mail, chat rooms, instant messaging, remote screen sharing, and multiplayer video games (in particular multi-user dungeons (MUDs) and dungeon crawlers).

Wikipedia also documents a Timeline of Social Media.

Wikipedia also draws a distinction between social media as mentioned above and social media platforms, that were enabled with the arrival of connected hypertext software in 1991, i.e. the arrival of the World Wide Web.

Wikipedia provides a List of Social Networking Services.

A technical term often used to describe the board topic of social media platforms or sites is "computer-mediate communication", or the way technology supports pre-existing social networks and how it helps strangers connect based upon shared interests, political views, or activities. It also includes how some platforms attract people based upon common language or shared racial, sexual, religious, or nationality-based identities. And this means also looking at how platforms incorporate new information and communication tools, such as mobile connectivity, blogging, photo/video-sharing, etc.

Wikipedia provides a List of Notable Blogs having Wikipedia pages, and a List of Image-Sharing Websites.

Wikipedia also provides a wide range of background pages on topics such as citizen journalism, citizen media, citizen science (list), collaborative filtering, collaborative journalism, collaborative software, collective intelligence, computer-supported cooperative work, content moderation, cross-devices tracking, crowdsourcing (list), deliberative democracy, digital footprint, disinformation, e-democracy, emotion recognition, e-participation, fake news, forensic profiling, identity theft, interactive journalism, Internet manipulation, Internet privacy, microblogging, misinformation, network economy, network effect, online deliberation, online identity, open-source intelligence, PageRank, participatory culture, participatory justice, participatory media, personalised marketing, podcasting, privacy concerns, public participation, reality mining, recommender system, reputation system, right to be forgotten, sentiment analysis, sharing economy, smart mob, social bookmarking (list), social peer-to-peer processes, social translucence, social genome, spamming, surveillance capitalism, swarm intelligence, targeted advertising, trust, trust metric, ubiquitous computing, virtual economy, virtual volunteering, virtual world, Web documentary, Web tracking, wisdom of the crowd,…

The above list just scrapes the surface of what touches in one way or another the topic of social media today.

Initially I think experts drew a tighter line between social networks that enabled people to make visible "latent ties", i.e. communicate with people who were already part of an extended social network, and those social networks that emphasised relationships between strangers. Both required the creation of a profile and both created/exploited some form of list of "friends". For example, SixDegrees.com, created in 1997, listed friends, family members and acquaintances, and LiveJournal was started in 1999 by someone who wanted to keep his school friends updated on his activities. On the other hand in 2000 LunarStorm looked to extend a Swedish digital online community called "StajiPlejs" dating from 1996. In 2001 it tried to fund itself through banners and other advertising, and also in 2001 BlackPlanet targeted matchmaking and job postings for African-American's.

It was already in 1989 that Tim Berner Lee’s developed a protocol to link hypertext documents together into what became known as the World Wide Web (WWW). In 1993 came Mosaic, often considered the world’s first graphical web browser (Netscape Navigator was the commercial derivative dating from 1994). WWW made an important contribution to the emergence and development of the concept of social media. Web 1.0 technology covered the period 1991 to about 2004 and was largely focussed on uni-directional communication where the user could just consume the content provided by a creator. Features allowing users to contribution to content, enrich it, modify it, or comment on it was very limited or inexistent. Web 2.0 (post-2004) technology provided the ability to actively participate irrespective of geographical distances and different time zones. Web 2.0 is interactive and user-generated content such as blogs, citizen journalism, peer-to-peer media distribution, video and photo sharing websites among other things. Web 3.0 targets the Semantic Web, i.e. to make Internet data machine-readable.

According to experts SixDegrees was the first recognisable social network site, because it had profiles, and in early 1998 lists of friends which could be surfed. The service closed in 2000.

It was in early 2001 that Jimmy Wales defining the goal of making a publicly editable encyclopaedia, and Larry Sanger is credited with the strategy of using a wiki to reach that goal. The domain wikipedia.org was registered on January 13, 2001, and Wikipedia was launched on January 15, 2001.

We had to wait until 2003 to see the arrival of LinkedIn and MySpace. Flickr appeared in 2004, YouTube appeared in 2005, and Twitter and Facebook (for everyone) appeared on 2006 (Google goes back to 1998). We tend to forget the failures, such as Orkut from Google (2004-2014) and Live Spaces from Microsoft (2004-2011).

It's important to remember that SixDegrees actually combined features that already existed, e.g. profiles existed on most major dating sites and many community sites. Buddy lists of AIM (1997) and ICQ (1996) supported lists of friends, although those friends were not visible to others. Classmates.com (1995) allowed people to affiliate with their high school or college and surf the network for others who were also affiliated, but users could not create profiles or list friends.

After Facebook came Reddit (2005), Spotify (2006), Tumblr (2007), Foursquare (2009), WhatsApp (2009), Pinterest (2010), Instagram (2010), Snapchat (2011), TikTok (2016),… In parallel in 2007 Apple introduced the iPhone with a touch screen and Internet browsing, and in 2008 the App Store opened. This meant that from then on all social media platforms had to work on smartphones as well.

I, like many others, would argue that a lot of the things that are included in the topic social media occurred before 1997. Some experts are willing to go back to 1792 and the telegraph used to transmit and receive messages over long distances. Others support the idea that the radio and telephone were used for social interaction, albeit one-way with the radio. Phone phreaking from the 1960s has also been mentioned as a social media precursor because people would hack into unused corporate mailboxes and host blogs and podcasts.

Telnet was developed in 1969 as an application protocol to be used on the Internet or local area network to provide a bidirectional interactive text-oriented communication using a virtual terminal connection.

The File Transfer Protocol (FTP) dates from 1971 and is a standard communication protocol used for the transfer of computer files from a server to a client on a computer network.

In 1971 the first network e-mail was sent, introducing the now-familiar address syntax with the '@' symbol designating the user's system address. It was a certain Charley Kline who sent the first host-to-host message "lo" on October 29, 1969. Some experts argue that email was not intended for the public production and distribution of content, and as such was not a social media, however listserv software (ca. 1984) used for managing email lists made individual-to-individual private communication more public and thus more social. So email sits in a hazy zone between public and private, and thus between individual and social media.

A precursor to the public bulletin board system was Community Memory, started in August 1973. The first public dial-up BBS was developed by Ward Christensen and Randy Suess, members of the Chicago Area Computer Hobbyists' Exchange (CACHE). The Computerized Bulletin Board System (CBBS) officially went online on February 16, 1978. It's worth mentioning that in 1988 Internet Relay Chat (IRC) was created to replace a multiuser talk program on a BBS.

Newsgroup experiments first occurred in 1979. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis of Duke University came up with the idea as a replacement for a local announcement program, and established a link called USENET with nearby University of North Carolina. It started with people offering news and informative articles, and by 1983 it was being used in Europe, and people were discussing everything from philosophy to films. Usenet was the first Internet community and the place for many of the most important public developments in the pre-commercial Internet. It's protocols and interface institutionalised a number of core elements of social media that persist to this day, such as topical forums, subject lines, posts, replies, and the resulting forms of message threads and subthreads, including branches to new threads, sub-forums, and different forums.

Wikipedia includes a List of Internet Forums (derived from BBS and Usenet).

In 1980 the Minitel, a videotex online service, was rolled out experimentally in France (it was retired in 2012). In 1981 CompuServe offered a video-text-like service allowing personal computer users to retrieve software from mainframe computers over telephone lines (they had already introduced an online text chat system in 1980). Bildschirmtext was a similar system launched in West Germany in 1983. Prodigy was an online service that ran from 1984 through the end of 2001, and GEnie ran from 1985 through the end of 1999 (both were created as competitors to CompuServe). Just as social media does today, all of these services provided different ways for regular users to produce and publish content, as well as to connect, circulate, and comment on others’ content in a variety of ways.

The modern blog evolved from the online diary, where people would keep a running account of their personal lives. Justin Hall, as a student began eleven years of personal blogging in 1994, and is generally recognised as one of the earliest bloggers, as is Jerry Pournelle. The term "weblog" was coined by Jorn Barger on December 17, 1997. The short form, "blog," was coined by Peter Merholz, who jokingly broke the word weblog into the phrase we blog in the sidebar of his blog Peterme.com in April 1999.

Conventional search engines existed which ranked results by counting how many times the search terms appeared on the page. Larry Page and Sergey Brin theorised about a better system that analysed the relationships among websites, and they called the algorithm PageRank. Page and Brin originally nicknamed the new search engine "BackRub", because the system checked backlinks to estimate the importance of a site. Eventually, they changed the name to Google, and the domain name www.google.com was registered on September 15, 1997.

Amazon started selling music and videos in 1998, and expanded to video games, consumer electronics, software, toys, etc. in 1999. Fairly early on it allowed customers to rate and review books and other products, creating a social media phenomenon that grew to encompass an entire genre of funny reviews. Amazon embraced social media and incorporated online sociality into its retailing experience, letting consumers satisfy a wide range of social, communicative, emotional, and identity-focused needs, including witty repartee, social commentary, personal revelation, self-promotion and even revenge-seeking.

As the Internet grew throughout the 1990s, it was becoming increasingly obvious to academics, programmers, entrepreneurs, and others that more and more people were going online for activities that were much more than just library-like exchanges and market-like transactions. And there were already a range of platforms and software applications that offered numerous different sorts of social experiences such as live (single and multi-user) chat, (some massively) multiplayer gaming, email lists, and message or bulletin boards.

Already in 1992-93 one expert noted that people were creating "virtual communities" in which they "exchange pleasantries and argue, engage in intellectual discourse, conduct commerce, exchange knowledge, share emotional support, make plans, brainstorm, gossip, feud, fall in love, find friends and lose them, play games, flirt, create a little high art and a lot of idle talk". However, since then the term "virtual communities" has been criticised as being overly academic and suggesting that new forms of social connection are not quite real. I'm not sure there is a clear conclusion about what electronic communication is really, except possible that the question has become irrelevant. Increasingly there are no offline equivalents of some forms of social media, so a comparison becomes meaningless, e.g. what is the offline equivalent of a verbal-video restaurant review or of user-generated music or video content…

One interesting alternative way of looking at the definition of social media is to look at the what the different competing definitions don't really include, for example:-

Accessible through apps and not (only) through websites, e.g. WhatsApp, or Facebook, which makes the "social media site" idea too narrow

Always online through notifications in desktop applications and on mobiles, which is usually not mentioned and is more than just "present" since it can become "intrusive"

Integrated and Media Rich, which goes well beyond simple "interaction"

Supports "passive sharing" of content when information is pushed towards users without the creator actively doing that, which extends the "relationship" beyond an explicitly made connection.

Naturally the question arose about the difference between social media and social networking. Social media could be seen as a media which is primarily used to transmit or share information with a broad audience, while social networking uses the platforms to engage with people having common interests and build relationships through community. Other experts consider social media as simply a system, a communication channel and not a "media location" that you visit. In contrast, they see social networking as two-way communication, where conversations are at the core, and through which relationships are developed. In this way Google and Facebook at social networks or platforms, they provide a service that brings together content producers (social media) with potential customers, just as traditional news media brings together readers and advertisers.

Again I'm not sure all this matters. Digital platforms give people (content producers in the broadest sense) access to substantial audiences, while search engines and social media engage global audiences almost instantaneously. Sites like Buzzfeed (2006), Upworthy (2012) and Vox (2014) have all been successful in creating viral content. Today consumers have access to an unprecedented array of content, and can almost as easily become producers themselves, as seen by the emergence of terms such as "prosumer" or "produsage". Instead of issuing press releases and offering spokespersons for interviews with television, radio and newspaper reporters, companies and public administrations can simply publish straight to Facebook. Also, in a positive way, the "voiceless" can express themselves and audiences can become empowered as citizens and creators. Social networks don't produce content, but they do distribute it, and they can shape the agenda by defining what is and is not acceptable content.

There is always a "but". Today professional information produces (e.g. newspaper and magazine publishers) are losing customers and money, and gaining very little from digital media alternatives. The reality was that most sources of reliable and timely information were funded by advertising, and online advertising spend is now dominated by Google and Facebook. In addition, since the US presidential election of 2016, the issue of "fake news" continues to challenge the credibility of professional information produces (e.g. journalism and news media). It doesn't help that some public figures dismiss any kind of unsympathetic coverage as "fake news". Perhaps news is really "novelties", i.e. just anything that is new, and is no longer "the first draft of history". Maybe social media and networking should focus on "soft" news, such as feature articles, entertainment journalism and human interest stories, leaving journalists to investigate and produce "hard news", i.e. "news that someone wants suppressed".

Is there something called a "factual account", was there ever? What about journalistic objectivity, or is every story just an augmentation of someone opinion? But what of informed opinion (and uniformed opinion)? Is there still a clear boundary between news and advertising? What about in the "public interest"? Do journalists still own the watchdog role and the practice of "public interest" journalism? Are journalist still the "watchdog of the state", and can they still topple governments and expose injustice? What is news worth, and should it simply be priced like consumer goods?

Do any of these questions matter, since Google, Facebook and TikTok will do what they want when they want to, and ask pay the fines if they get it totally wrong.

What's next?

What is certain in the minds of most experts is that TikTok will further expand as a social mainstay and trends incubator. What made TikTok so popular and gain traction over the past few years is the democratisation of storytelling and how people can use TikTok features to create short videos with no editing background. With the attention span decreasing year over year, the use of "micro-content" that grasps attention will increase, as well as the use of looping videos, remixing, voice-overs, music and punchlines at the end of the content. It has been reported that TikTok now beat YouTube’s average watch time for Android users in the US despite only allowing for short-form content. But additionally, the platform algorithm is somehow different from other social media platforms in the sense that it relies on "authority ranking", measuring the influence and authority of someone in their specific vertical domain. When done right, TikTok content can generate thousands of views even for creators that have only a few followers. In addition its AI-powered algorithm boosts content towards users that crave similar content through the "For You" entry page (the discovery section of the app), and even if the content looks amateurish. Today, TikTok is forcing its new competitors to adapt to the threat, e.g. Instagram has decided that it’s no longer a photo-sharing app and is now heavily promoting the use of Reels, a copycat of short-form content born on TikTok.

As a consequence of TikTok’s growth, the notion of influencer has evolved, moving from somebody with huge following and sometimes questionable reach to somebody that achieves great reach without having specifically loads of followers. In the new social media distribution economy, authority and reach will overwrite followers and the traditional notion of engagement.

Social Commerce has been around for years, bolstered by Asian super apps, accelerated by the pandemic and better mobile and connectivity logistics. Building on tighter consumer expectations and the search for an "experience", brands have activated channels to drive sales and offer their clientele additional ways to discover and personalised services, without leaving the brand app. Social networks clearly understood this and have started to introduced numerous shopping features, most notably product tagged posts and social storefronts. Over time the public will become more acclimated to the concept, and algorithms will get smarter, but there is still a long way to go. You have to remember that more than 50% of younger people use social media for product research. Social shops track and target the behaviour of visitors, and the key is to activate a first purchase and then focus on repeat business. So-called micro-influencers through live-streaming events, deeper engaging video content, gamification, etc. can drive impulse and realtime buying.

Social audio is already present in the home with Apple, Spotify and Clubhouse, and podcasts continue to be successful in providing valuable and entertaining long-form content. We know that podcasts are surprisingly successful in influencing consumers habits, and nearly ⅓ listen to podcast content related to their hobbies. In particular sponsored podcasts represent a new way of reaching 18-44 year-olds with interesting content at a time where ads have a hard time convincing them. Social audio also includes music, and on TikTok short-form video content is often associated with songs that have the power of turning the videos into overnight successes. And TikTok provides a 150,000 royalty-free tracks library sourced from emerging artists and music houses.

Originally brands with active social communities benefited from a strong engagement and a high level of interaction. Now brands that may "own" large communities can't reach them in the same way. Part of the problem was that brands focussed on attracted "fans", who then turned out to have very little connection with the brand itself. The challenge today is to build a social community, to listen and understand customer conversations, to focus on customer retention and loyalty, to help customers answer the questions of other customers, and generally to collaborate more closely with the community and learn how that can contribute to product and services improvement or even additional engineering options.

I don't like the term "metaverse", but it appears to be becoming a reality. In its simplest form the metaverse is just the convergence between digital and physical. A centrepiece is the shift to web3 (not the same as Web 3.0) with a crucial role for software and hardware (phones, smart devices and headsets). It’s not an actual network with a URL but something that looks to integrate virtual reality, augmented reality, gaming, music, art, education, work (from home), fashion and crafts, etc., all operating in a decentralised way, employing blockchain technologies, and some form of token-based economic. Because the whole concept is based upon sharing among users, social is supposed to be at its core, and as far as I can see the (first) target is the Gen Z, i.e. those born in mid-late 1990s.

What appears certain is that more and more people look to social media for entertainment, information, conversations and commerce, and they spend a lot of time doing so (various sources report an average use of social media of more than 140 mins per day). Data shows a correlation between video view rate and purchases, but more importantly consumers are more likely to act when brands provide an experience, taking them on a journey that goes beyond a static product post. What has emerged is that more than 60% of TikTokers like brands more when they can create or participate in a trend on the platform. What appears equally true is that people appreciate things that happen naturally and unpredictably (as opposed to being pre-scripted). Suggestions for the future is that brands must "lean into and participate in trends, to connect through conversations and co-create, all of which builds advocacy and ultimately drives purchases". So instead of planning content across the whole year and strategically choosing calendar moments, marketers should rethink the newsroom model and how fast they are able to jump on trends and create relevant content.

The final point is that new it's "how" and not "should" a brand partner with influencers (again I'm not convinced). The trend to move away from bland endorsements to authentic storytelling is projected to increase. More than ever equality matters to consumers, and these consumers see through the brands that just try to check the boxes, e.g. diverse casting or piggybacking on specific themes. That looks to be a very positive trend. It would also appear that the move will towards more experience-driven influencer-generated content across livestream and video formats, whether or not including product tags and checkout options. The role of the influencer is now stable, because companies can now measure their impact as a return-on-investment, and it looks as if an influencer properly integrated into a wide campaign can add up to 30% on the investment made (not sure I believe that).

Biggest social media problems today

Perhaps the biggest challenge to both traditional media and social media is "fake news". Whatever our source of information, etc. we would like to trust it. But fake news is shaped to replicate "true news" by mimicking its characteristics (i.e. accuracy, verifiability, brevity, balance, and truthfulness) with the aim to mislead the public. Today all forms of news media has been hit particularly hard by the rise of fake news. Originally it was a term used to describe satirical sites, doctored photography, fabricated news, propaganda, etc. Some experts have traced back the origin of fake news to at least Roman times when Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, used fake news to encourage the destruction of the republican system. Today some experts see fake news as a kind of infectious pathogen, where social media is the host that spreads the pathogen.

The role of fake news changed during the US election of 2016. Initially, it was used to describe the no-frills sites that parroted the conventions of online news, but contained sensationalised stories to attract advertising dollars. The term was then invoked in reference to hyper-partisan but not necessarily misleading news sites such as Breitbart, and it further expanded when presidential candidate Donald Trump used it to describe unsympathetic news coverage. Studies have shown that falsehoods actually diffuse significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information, and the effect is even more pronounced for false political news than for false news about terrorism, natural disasters, science, urban legends, or financial information.

But fake news is not the only problem.

Web 2.0 technologies and the emergence of participatory journalism has moved everyone from a world of "limited information" to one of "overwhelming, often unprocessed, information". This obviously emphasises the role of journalists and news organisations as creators of effective and reliable information, in an information-rich environment. Newcomers need to learn how to organise, rationalise and systematise the production of information, and a fast moving market might not give them the time to do that. Perhaps combining reliability and stability may be essential for both information and social medias. However, when some argue for stability, others argue for adaptability. No matter what, a new parameter has emerged, namely "engagement". Sharing/engagement has created new practices and requirements, i.e. knowing how to deal with comments, retweets, fans, friends, favourites and followers. And sharing on social networks has become a major distribution mechanism for content. Today this is all about the tools that enable all sorts of websites, e.g. some sites look like news sites, some don’t, but they all enter the same information space. The audience has in many cases become a primary driver of what is reported, posted, published and shared. Social media tends to reward content that is shorter, more visual and more emotive, yet search engines return near-identical results for popular stories produced by different providers. Meanwhile, "content farms", which specialise in producing "questionable, low-quality content designed to go ultra-viral" are also often just as successful. Remember, false news spreads faster and further than true news. Both cognitive scientists and media scholars have found that the more people are exposed to untruths, the more likely it is that those people will believe them. Technology and the use of third-party platforms for distribution, allows producers of false information (fake news) to make their product formally and functionally indistinguishable from professional journalism.

Underpinning the rise of engagement as a core value is a new feature of the information landscape, namely the "atomisation" of information. In many cases, the information has been decoupled from its source. It has been broken down into its constituent parts, so that it is now distributed and consumed on a story-by-story basis, rather than as one among several. This is one effect of separating out the roles of information producer and information distributor, and in the same way that the music industry has seen albums replaced by individual tracks, so too an edition or news bulletin has been replaced by individual items of news. And just as the music industry has been disrupted, so to the information industry. In a modern (digital) newsroom, success is now gauged on a story level. What might have previously been a page, site, edition or show is now fragmented into discrete units, with each unit’s success measured in minutes and hours, not days and weeks. And, as already mentioned, soft news tends to flourish in this environment. However, the platforms differ from one another. The original architecture of Twitter did not include any algorithmic filtering based on user preferences, which made the platform suited to hard news. This was not the case with Facebook. A hard piece of news might have dominated Twitter, but would have been almost invisible on Facebook, simply because it was not "like-able" and even harder to comment on.

Today’s online news consumers are more likely to come across content that creates strong emotions, particularly surprise, content that is more personal and affective, and content that is visually arresting. The content is also likely to be shorter in length, so for example this penalises investigative journalism which is time-consuming and expensive, and is often reported in long form. Both factors, cost and length, pose challenges given that online platforms provide less profit per reader than traditional media. Also, the competition for audience attention, driven largely by social media platforms, makes it difficult to get, let alone keep, readers’ attention. To increase the "click-through rate" for individual stories, headlines are rewritten to emphasise sentimentality. The technique works at attracting eyeballs. These content effects are particularly pronounced for digital only information providers whose distribution system depends on atomised news delivered through social media and search. This type of content creator is more likely to accept commodification, i.e. the belief that every individual piece of writing is its own stand-alone mini-profit centre, and success is measured in shares, likes or tweets or the direct income a piece brings in.

The widespread use of digital platforms, and particularly social media, means that information providers content, and also their competitors' content, is hypervisible online. This can have the effect of homogenising content, as content creators follow each other’s leads, in a kind of groupthink where coverage of major events is likely to be the same irrespective of source. Hypervisibility inevitably leads to a keen attention to the clicks and shares generated by each story. Content creators are reduced to competing just on the popularity of the content, not the quality of the content. This can create incongruous situations. Everyone knows that consumers will arrive from links on platforms such as Google, Facebook or Twitter, and they can just as easily navigate away again. Everyone is measuring how well their stories performed, and they are quick to copy the successes of others or churn their articles that were successful in the past.

All is not negative since several successful content creators, including Buzzfeed, have used social media success to fund significant investigative journalism. Social media is not just a distribution tool, it also helps to create diverse and quality content by putting creators in touch with a wider range of sources and perspectives. We can see the flip-side of this conflict emerging as digital native news organisations such as Buzzfeed and Vice, which have already achieved substantial market success by following the consumption demands of audiences, new seek to accumulate cultural capital in the field of hard information. They hire experienced content creators to produce high quality content they hope will translate into peer recognition. This strategy enables them to accumulate two different forms of institutional resources from two fields with opposing logics, i.e. ongoing accumulation of economic capital, based on number of users, advertising sales and profits, and cultural capital based on the legitimacy, credibility and prestige cultivated by values-driven content production.

It's all about algorithms

Algorithms are a set of specified rules and protocols enabling a system to act autonomously. Digital platforms employ various algorithmic methods to produce and curate information to optimise engagement. Indeed, innovations often involve both periodical and significant changes to algorithms. Such changes most obviously affect the distribution of content, but they also have significant effects on production and consumption. For information consumers, algorithmic systems can provide significant benefits. In 2016 it was said that approximately 90% of data on the Internet has been created in the past two years (IBM 2016). The increase in the quantity of information available online has been unprecedented and dramatic. Methods to search, sort and filter information are fundamental, and the capacities of algorithmic systems to filter the abundance of content are immense. Without algorithmic systems, access to recent, relevant and important content would be considerably more cumbersome (its all about "personalisation"). Algorithmic systems also provide benefits for content producers. They can help them identify important stories on social media platforms and they can help them use data sets to generate stories. Digital first publishers, whose business model is built on atomisation, rely heavily on social media distribution for their audiences, and along with public broadcasters, they are particularly reliant on social media algorithms. For public broadcasters, social media algorithms, if exploited properly, can help them fulfil their mandate by granting access to traditionally hard-to-reach audiences.

Aside from these benefits, there is also a downside. This includes the way everyone is required to devote considerable resources to accommodating the ongoing algorithmic changes made by digital platforms. In 2016, Facebook began implementing a "pivot to video", in which the social network encouraged news publishers to produce more video content. For a time, Facebook paid news publishers to experiment with video so as to offset high production costs, but the result was a rush of poorly produced content, in part due to contractual clauses imposed on publishers specifying the number of videos to be produced each month. Once implemented Facebook abolished "the carousel", which combined native video on Facebook with accompanying articles that directed traffic straight to the original news website. So news publishers stopped providing videos, then Facebook rolled out Facebook Watch, a video on demand service to rival both Google’s YouTube and traditional TV broadcasters.

Other changes have had a mix of positive and negative effects. In January 2018, Facebook announced changes to its newsfeed algorithm that significantly affected news content. The changes involved prioritising "meaningful content" posted by friends and family over news, videos and posts from recognised content brands. As a result, the amount of news overall on the platform shrank from 5% to 4%. Then Facebook decided to prioritising content that was "trustworthy". To determine trustworthiness, Facebook now asks its US users, in the course of ongoing quality surveys, whether they are familiar with a source, and whether they trust that source. This suggests that larger organisations are being favoured by these and other algorithmic changes, as some smaller but valuable content providers almost disappeared from most social media feeds. Facebook argued that the changes prioritise quality over quantity for news and reduces "clickbait", so there was a reduction in the amount of news available but what was there was of a higher quality. Other algorithmic changes in the US have given further priority to local over international news. Some content providers have described this as playing a cat-and-mouse game, as they try to balance their strategic autonomy with ongoing attempts to adapt to the algorithmic innovations of platforms. The attempt to produce algorithm-satisfying content is sometimes referred to as "gaming the algorithm". To satisfy social media and search engine algorithms, for instance, content producers and publishers are increasingly trying to produce content with maximum "shareability". At its best, gaming the algorithm can ensure high quality content receives the online distribution it deserves. However, it also means that many content developers are engaging heavily in story-by-story optimisation. This takes significant technical investment, which some smaller content developers struggle to resource.

The migration of news content to digital channels, and the attendant atomisation of news and impact of constant evolving algorithms, has caused a shift from mass communication to personalised and customised content consumption. Personalisation, in this context, is a digital process that involves searching, sorting and recommending content based on the explicit and/or implicit preferences of individual users. Customisation refers to the modification of sources, delivery and frequency of digital content for individual consumption. Both personalisation and customisation help to filter the abundance of digital content and to present information tailored to the interests of the individual. For example, people are increasingly dependent on algorithms which "autonomously" select the news content they consume (and the algorithms are used both by digital platforms and by traditional news media).

The purpose of algorithmic personalisation is to optimise user engagement by increasing the consumption of content items per user. This aligns with the nature of internet advertising, where granular details on user preferences are gathered to create comprehensive user profiles. These profiles allow digital platforms to sell targeted advertisements and to personalise content that engages the user. Digital profiles can include preferences that are explicitly made by the user, such as "likes" and "shares", but can also include implicit preferences, such as recommending content that has engaged people with similar profiles.

Digital platforms and digital content producers rely on "recommender systems" to filter content. Such systems prioritise and personalise content based on recorded or inferred user preferences (this is often called content-based filtering). The ensuing recommendations are designed to assist the user’s decision-making process in the consumption. Generally, recommender systems collecting user preferences to build a profile (or model) that is used for prediction. They "learn" from the feedback data gathered about the user and adapt the profile (or model) of the user. They then predict or recommend content that the user may prefer, based upon both explicit feedback and probabilistic inference. So recommender systems end up suggesting content similar to items that the user has explicitly liked or engaged with in the past. A significant problem with content-based filtering, however, is its dependence on metadata, i.e. the richness of the content descriptions that are required before useful recommendations can be made.

Another way is collaborative filtering, where systems learn to recommend content that other users with similar preferences have liked or engaged with in the past. The recommendations are calculated based on the similarities between user profiles, such as user behaviour or ratings history. A significant advantage of collaborative filtering is that it can perform well in domains where it is difficult to accurately label content (such as opinions). Collaborative filtering systems can also generate useful recommendations even when content is not explicitly listed in a user’s profile. Challenges can emerge, however, when inadequate information is known about the user or the content, which results in irrelevant predictions. Of course you can try to combine both approaches, utilising the advantages of one method and compensate for the weaknesses of another. This allows hybrid systems to base their recommendations on both content and similar profiles that have engaged with the item. Digital platforms including Google, Facebook and Twitter are secretive about the details of the workings of their algorithms. Their algorithms have been described as the "black box", or "secret sauce", of their services. One such approach is called Collaborative Topic Modelling, or CTM. The CTM method works by modelling content to determine its topic(s), then adjusting the model by gathering signals from readers, such as "clicks", and then modelling reader preferences from interactions with the platform, and finally making recommendations based on the similarity between content and preferences.

It's really interesting to delve a little deeper into how a CTM model works. The first step is to figure out what the content is about, e.g. what's the topic of the article or new item. Natural Language Processing (NLP) can be used to counts the number of times a particular word appears in an article and compare it to other articles. This enables the algorithm autonomously to determine the topic(s) of the article, e.g. it knows how to relate "Parliament" to the topic of "Politics". It determines how much an article is devoted to a particular topic, and if multiple topics are present in an article (referred to as "weightings"). There can be problems when the language used is ambiguous, e.g. the use of puns and metaphors in satirical articles can make it difficult for a system to correctly categorise content. A hybrid approach can introduce other priorities based upon factors such as reading patterns, recent content, word length, specific words, etc. Topic-modelling can use the articles someone has read to establish a baseline of the user preferences. "Click-through's" can also be used, but one key point is to "back-off" from over predicting. By providing a conservative estimate of user preferences, means that the system can exposes readers to more serendipitous recommendations. The systems can also incorporate more granular user information. Analytics are collected on reader behaviour such as scroll depth, article dwell time, media sharing patterns, etc., and this means that a more complete model of a user preferences can be built. To train the algorithm to account for these evolving preferences, a subset of the readership is selected, along with their labelled attributes and preferences. Supervised Learning (a type of Machine Learning) techniques are then applied to help make predictions on what a user wants to read based on their recorded preferences. The algorithm then iteratively improves its classification and recommendation abilities (or "learns") as it is trained on more data (both user preferences and news and articles) and as its algorithmic weightings are tweaked. This process of modelling topic content and user preferences allows the system to provide personalised news recommendations. It enables the abundance of online content to be filtered at an individual level, and it improves with greater user interaction. These system have become widespread since about 2015.

Everyone who runs some kind of digital platform, including search engines, social media and content aggregators, apply algorithms to personalise the content offered to a consumer, but the consumer can also customise the content they want to receive. Customisation refers to the modification of sources, delivery and frequency of digital content for individual consumption. Customisation, like personalisation, is in part a response to the way in which digital media has expanded the possible channels by which users can consume news content. That is, the proliferation of digital devices, in concert with the accelerated news cycle, has created an increasing range of options for content consumption. This had led some to argue that an abundance has been superseded by an overabundance of options, leaving some consumers overwhelmed or even "bombarded and bewildered". However, social media is founded on a principle of customisation, i.e. users choose their friends on Facebook and who they follow on Twitter. So the content encountered is largely determined by whatever is shared by those who have been befriended and followed. In addition most social media providers allow consumers to customise their settings, so in fact individual consumers are now able make the sorts of curatorial decisions formerly reserved for editors of traditional content providers. Of course, this assumes that individuals have the knowledge and abilities to make responsible content consumption decisions that are in their best interests. Given the lowered barriers of access to content for consumers, information literacy becomes more important as users are increasingly required to check facts, monitor the reliability of sources and keep an open mind by consuming a diversity of sources.

Why do content providers go to all this trouble to build and continually optimise algorithmic techniques for their content. Firstly, they need themselves to sort through the abundance of content produced every day. Secondly, they need to recommend interesting content that users will consume, and which will keep them engaged with the platform. This is done by gathering information on users, selling that information to advertisers to generate revenue, and then providing personalised content via algorithmic methods to engage individual users. Greater user engagement logically leads to greater opportunities for advertising revenue for digital platforms. As one expert wrote, "YouTube and Facebook take no interest in what the content is about, whether it’s holocaust denial videos or makeup tutorials; they are simply interested in keeping their viewers on the platform". What counts is to host content that attracts attention, and the concept of "public interest" is irrelevant. To maximise engagement consumers are increasingly having their content filtered to reflect narrow, personalised interests. And when digital platforms are incentivised to show content that optimises engagement, consumers can find themselves in algorithmically constructed "filter bubbles". These filter bubbles are personalised according to user preferences, and then further reinforced by customisation. These cycles of personalisation and customisation, it is argued, exacerbate the tendency of people to consume content that conforms to their existing worldviews, which thus creates "echo chambers". The potential implications include a constrained public discourse, a less informed citizenry and sharpened political polarisation.

Filter bubbles and echo chambers

Being exposed to a diversity of content, e.g. quality news items, is supposed to ensure a well-informed citizenry. You want people to received a diversity of sources, content, and perspectives, but algorithmic filtering methods run the risk of constraining diversity, which may cause "information blindness" for consumers. It's possible that the algorithms have a filtering effect which artificially reinforces a users preferences and perspectives. These "echo chambers" can lead people to avoid important public issues altogether or can polarise public discussion and thereby inhibit constructive debate. However, algorithms do not necessarily limit diversity by definition. In fact content diversity can be programmed into a platforms' algorithms. There is evidence that for news stories most users receive very similar recommendations, despite having different political opinions. The situation in not likely to be same for social media platforms such as Facebook, where news items mingle with non-news items, and where user experiences are necessarily more individualised.

However it's worth noting that there has been a dramatic increase in the quantity of news content. In part, this is driven by the rise of both social media and search platforms, which require that websites have a steady stream of new content to remain competitive. There is also a growing amount of robot-produced journalism content. In addition many hard news stories are now written quickly, with little, if any, original reporting. Today online news had moved towards becoming a generic commodity, with news outlets differentiating their stories only by cosmetic differences in headlines and lead paragraphs. And it is not certain that an increased quantity of news stories equates to increased content diversity, many "new" stores are just follow-ups of past items. The reality is that the speed and churn of the online environment, makes follow up stories easier and quicker to write than original content.

Algorithms can filter and prioritise news in much the same way as human editors, meaning that they can promote diversity, or to limit it. In other words, code and algorithms can be just as excellent as human editors, and just as lamentable. Fortunately many digital platforms have changed their algorithms in the wake of the outcry over "fake news", i.e. they are trying to integrate notions of trust and quality in response to political and consumer demands to fix the reliability of information in their systems.

A further point here concerns a potential excess of choice. On the Internet, news consumers have access to an abundance of information and sources. This is potentially problematic, given that research has shown that when people are confronted with too many choices, they regularly make bad choices, or are paralysed into making no choice at all. What's more, they are often left feeling dissatisfied with those choices. This has been described as the "paradox of choice", i.e. presenting more options can lead to worse choices and lower satisfaction. This paradox has been confirmed for search engine results, where participants whose searches returned six results made better choices and were more satisfied than participants whose searches returned 24 results. Choice is a difficult subject, since for example an enormous choice of novels may not be overwhelming.

Just as the effects of algorithms on content diversity remain unclear, so too it is unclear whether algorithmic techniques are fostering a constrained public discourse, a less informed citizenry and exacerbated political polarisation. This lack of clarity may be due to the relatively recent rise of algorithmic systems, the difficulties and methodological shortcomings of measuring their effects, or simply, that theories of filter bubbles and echo chambers are exaggerated. Further, these negative effects must be weighed against the benefits that algorithmic systems provide to news consumers, including the ability to search, sort and filter masses of online news content. What is clear is that the prevalence of algorithmic systems in digital news media is wide and growing, and that their effects on content diversity and public discourse need to be understood better.

Compromised autonomy and constrained choice

Ostensibly, cross-platform availability of content promote autonomy when it comes to content consumption. However, some experts argue that algorithms, not autonomy, are guiding our actions and thoughts, or "The algorithms that orchestrate our ads are starting to orchestrate our lives".

Individual autonomy is all about self-determination, self-governance and self-authorisation, i.e. the ability to determine our own life and chart our own course. Do algorithms of search engines and social media compromise this? Do they compromise autonomy by limiting and channelling choice? A legal scholar wrote, " Whoever controls search engines has enormous influence on us all. They can shape what we read, who we listen to, and who gets heard". Evidence for social media’s adverse impact on autonomy emerged in 2014, when Facebook revealed it had manipulated the newsfeeds of nearly 700,000 users to see how adding negative or positive content affected the mood of users. The results of the controversial Facebook-backed study showed that "emotional states can be transferred to others via emotional contagion, leading people to experience the same emotions without their awareness".

For digital platforms, the underlying assumption is that the implicit preferences they attribute to individual consumers will become more and more accurate, so that they perfectly align with the choices of consumers. This reasoning suggests that if the algorithms are good enough, they will not compromise autonomy, because they will perfectly align with users’ choices and preferences. However, such alignment is difficult, perhaps impossible. Because algorithmic methods infer the implicit preferences of consumers, content can be personalised based on a consumers historical behaviour on the platform, similarities between consumer profiles and the profiles of others like them, and other inferred attributes. However, consumers might change their preferences over time, or they may in fact prefer content that diverges from the content received by people with similar profiles. A related issue concerns transparency, what if users do not know how those algorithms affect them? Won't their autonomy be compromised?

Transparency and accountability

The algorithmic systems that digital content platforms depend upon are often proprietary methods that are withheld from public purview. In the interests of keeping trade secrets, the full scope of how these algorithmic systems personalise consumer content remains opaque and removed from public criticism. This raises concerns about a lack of transparency and poor accountability. How well do consumers understand the processes behind algorithms and filtering?

While evidence to support the theories of "filter bubbles" and "echo chambers" remains inconclusive, consumers generally do not have a firm grasp on the application and extent of algorithmic personalisation in providing content. Consumers are largely unaware of how and whether digital content platforms track user preferences to make decisions on the delivery of personalised content. This is potentially problematic for platforms that don’t identify themselves as news organisations, yet increasingly host the publication of news content.

"Transparency" is the ability to view the truth and motives that underlie people’s actions as a means to strengthening accountability and trust. Algorithmic "transparency" provides insight into the operations of autonomous systems, but we still need content providers and content platforms to describe how certain input factors affect final decisions, outcomes, or recommendations.

Tellingly, transparency has evolved as a key ethical principle of news journalism, but how proprietary and ever-changing algorithms work is not transparent.

One for the pot…

Before we move on the real theme of this webpage, let me quote from a recent article "The Age of Social Media Is Ending" where the author Ian Bogost writes…

On social media, everyone believes that anyone to whom they have access owes them an audience: a writer who posted a take, a celebrity who announced a project, a pretty girl just trying to live her life, that anon who said something afflictive. When network connections become activated for any reason or no reason, then every connection seems worthy of traversing.

That was a terrible idea. As I’ve written before on this subject, people just aren’t meant to talk to one another this much. They shouldn’t have that much to say, they shouldn’t expect to receive such a large audience for that expression, and they shouldn’t suppose a right to comment or rejoinder for every thought or notion either. From being asked to review every product you buy to believing that every tweet or Instagram image warrants likes or comments or follows, social media produced a positively unhinged, sociopathic rendition of human sociality. That’s no surprise, I guess, given that the model was forged in the fires of Big Tech companies such as Facebook, where sociopathy is a design philosophy.

Moving on, how did I leave Facebook?

This appears to have become far more simple than in the past. Because Facebook actually publishes a page entitled "Deactivating or deleting your account". In addition you can also look at "Accessing and downloading your information".

Before deleting a Facebook account I decided to download a copy of the information stored on Facebook, including photos, videos, and more.

I followed the instructions provided by Facebook, and I chose the widest range of time, and the highest quality for the media, and made the request on 5 Jan 2023 at 16:48 and received an immediate confirmation email from Facebook. I received an email answer with the download ready at 16:59 on the same day. I asked for the download and was initially blocked because of the unusual activity on my account. This was perfectly normal since I had not used the account for some years. I was required to provide a security code sent to my email address, and then change my password. After that I was able to download my Facebook data.

My entire "Facebook life" was 180.2 MB with 692 items. The "master" folder consisted of a series of 48 folders and a web server directory index (index.html). A total of 23 of the 48 folders were "no-data.txt". These folders do not contain data that I deleted during my time using Facebook.

I found that I had registered in Facebook on 15 November 2008, and had more or less stopped any activity in 2018, so that makes 10 years of totally banal time wasting. I think my motivation at the time was that I had retired in mid-late 2007 and was hoping that, as I moved around Europe, Facebook would provide a decent platform to maintain relationships with family, friends, and ex-colleagues. I remember finding that many of those "friends" were not Facebook users, so it turned out to be less useful than I had originally planned.

Looking into my Facebook folders I was struck with what I called "interestingly banal" content. This included videos and shows I had visited, and the time I spent watching each of them (often less than 60 seconds). Then there were a few marketplace interactions. There were quite a number of visits to people's profiles, to events, and to groups. There were a small number of saved links, a few notifications, and a few events.

There were a surprising number of photos (328), and just 5 videos (however I shared links to 100's of videos). What was also a pleasant surprise was that a non-negligible number of the photos were not duplicates of ones already in my Photos collection.

Concerning what are called "group interactions", mine was dominated by a pro-European group, and a few local groups around where I was living.

I suppose Facebook is all about "Friends", but mine were a measly 30, consisting of a few family, some friends, and a couple of work colleagues (plus about 20 "removed friends").

The core of my Facebook activity were comments, 100's of them to friends and groups (and linked to photos and shared video links).

Perhaps the most intriguing folder was Facebook ads_information with "advertisers_using_your_activity_or_information". There was a very long list of "advertiser" tagged "A list uploaded or used by the advertiser". My "Interactions you may have had with the advertisers website, app or store" was ZERO or 0.00000… I have kept advertisers_using_your_activity_or_information just for reference.

In the past it was common to implement what was called "seeded" mailing lists. You would secretly add yourself, other company officers and possibly external contacts to your mailing lists. This would ensure that you received any emails distributed to the list, and keep key company executives and some business partners in the loop on business activities. In addition you saw what other recipients saw, and you could immediately see if your lists had been hacked. The "seed" idea can be extended so that ordinary records/files get secretly delivered back to the owner who can monitor usage, etc. If your lists or records are used by a variety of different services (internal and external) you see whom might be misusing the list or set of records. What Facebook does is to allow its advertisers to target people most like their established customers, this is the so-called Lookalike Audiences. What this offers is that Facebook takes several sets of people as "seeds" and builds an audience of similar people (the meaning of "seed" is different). This audience is a list of Facebook members that will be used for targeted advertising, even if they have not explicitly visited that advertiser. The real question appears to be that a lookalike audience can be built by a respected and credible advertiser, but there is no way for them to "seed" their audience to know if and when it is being used by someone else. The argument here is that legitimate advertisers would pay to seed their lookalike audience list, but Facebook does not provide that service (or allow anyone else to provide that service). The issue is quite complex, but this posting goes some way to describing the situation.

I guess I knew that Facebook also had access to data about its users' activities on websites and apps that were not affiliated with Facebook. I understand that it is possible in Facebook to use Hide Ad control, but I did not use it, and I'm not sure if it was available in 2018 or earlier. I certainly didn't know anything about Off-Facebook Activity settings. I, like most people, consider Facebook advertising controls are specifically designed so as not be in the users' best interest. So it does not surprise me that scam advertisers can highjack Lookalike Audiences from reputable advertisers, and insert themselves into a Facebook users list of advertisers allowed to use a person activity_or_information. Perhaps this is why my list is hundred of advertisers long, starting with such oddities as "Accessories" and "BM A 2174" though to "Tran Phong O" and "30007".

There were the usual folders for security information, profile information, preferences, and pages I liked and followed. I remember inputting a totally fictitious birthday of 1 January 1970.

Finally there were 10 folders with very little in them.

Here are the instructions taken from Facebook…

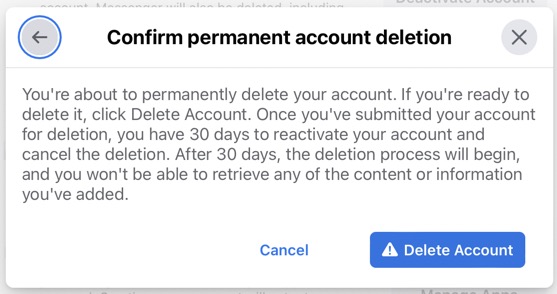

To permanently delete your account

I decided to permanently delete my Facebook account, and confirmed that decision.

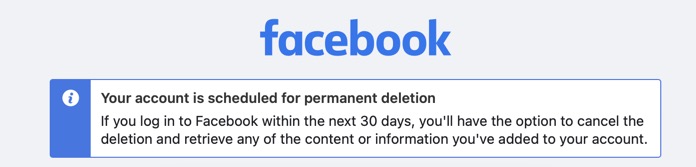

The permanent deletion process started and I also received an email informing me that after 30 days I would not be able to access my old Facebook account or any of its contents.

The only question left is how do I know that my account has been deleted. The obvious answer is when I cannot longer login to my old account, but that does not guarantee that all the data in the account has been deleted. Also it's important to realise that some types of content (like messages) have multiple recipients. When I delete a Facebook message it will still exist in other recipients' Facebook inboxes. Also some types of content are actually views of other content. For instance, if I deleted a news feed story about a photo, it removes the story from my feed but does not delete the actual photo. Also Facebook needs to keep a record of which user ID my account had so it isn't given to another user later.

Facebook claimed that all the data is deleted from their servers and backup systems, so they are unable to retrieve this deleted content. This means that the data on the servers is no longer protected (i.e. its unindexed), and will eventually be written over. However, they may keep service-related information about my account, like IP address logins or email changes. They write that this is done to protect my security, prevent abuse, and improve their services. Separately Facebook wrote that they keep log data forever, but it is not attacked to a specific name.

It's worth noting that Facebook has been audited by the US Federal Government and by the Irish Government, and they have confirmed that delete does mean delete, with the usual provisors as mentioned above.

I also had a second Facebook account attached to a different email address. My entire "Facebook life" was 774 KB with 124 items. A total of 30 folders were "no-data.txt". For some reason I has set up this account in May 2015, but it had virtually no activity, and no advertiser activity.

Moving on, how did I leave LinkedIn?

It looks as if permanently deleting my LinkedIn account, is more or less the same process as for my Facebook account. Except a permanent delete is called "Closing your LinkedIn account". It deletes my profile and removes access to all my LinkedIn information on their site.

As with Facebook its best first to download a copy of my data before closing account.

Request made Jan 6 08:40 no confirmation (24 hrs)

Joined Feb 12 2010

How LinkedIn uses your data

Settings Data privacy "Get a copy of your data leads" to "Export your data"

If you have a Premium account, you can cancel the Premium access, but still keep your free Basic account to retain your profile, connections, and other information.

To close your LinkedIn account from the Settings & Privacy page:

Click the Me icon at top of your LinkedIn homepage.

Select Settings & Privacy from the dropdown.

Under Account management section of the Account preferences section, click Change next to Close account

Check the reason for closing your account and click Next.

Enter your account password and click Close account.

You can also close your account directly from the Close Account page. Before you do, please note:

You won't have access to your connections or any information you've added to your account.

Your profile will no longer be visible on LinkedIn.

Search engines like Yahoo!, Bing, and Google may still display your information temporarily due to the way they collect and update their search data. Learn more about how your profile shows up in search engine results.

You'll lose all recommendations and endorsements you've collected on your LinkedIn profile.

You may want to download a copy of your data before you close your account with us.

If you have a premium membership, own a LinkedIn group, or have a premium account license, you'll have to resolve those accounts before being able to close your Basic account.

If you've created more than one account, learn how to delete or merge a duplicate account.

You can reopen your account in most cases if it's been closed less than 14 days, but we're unable to recover the following even if you reopen your account:

Endorsements and recommendations

Ignored or pending invitations

Followings (Top Voices, Companies, etc.)

Group memberships

Do you want to keep your account but receive less email and notifications?

You can set the frequency of email communications and notifications from the Communications section of your Settings & Privacy page to reduce emails, notifications, group digest emails, and LinkedIn announcements. On the mobile app, the Settings page is located at the top right corner of your profile page.

Learn more about managing the types and frequency of email from LinkedIn.

Are you having trouble accessing the account you want to close?

If you can't access the account you want to close, find out how we can help you get access to your email or reset your password.

What social media should I use, if any?

At least one source classified social media in five different groups:-

Social Networking (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn

Photo Sharing (Instagram, Pinterest + Ingur

Video Sharing (Youtube, Vimeo

Interactive Media (Snapchat, TikTok

Blogging/Community Building (Tumblr, Reddit + Etsy Blog, Wordpress, HunSpot, Medium

Then there are the Messaging apps (WhatsApp, Messenger, WeChat

Others (Goodreads, Quora, Flipboard, Yelp, Tripadvisor, Etsy, Faveable, Houzz, Whisper, 4chan,

Wants:-

Listening to live conversations on specific topics. - Clubhouse, Twitter Spaces, Spotify

Watching videos in short and long formats. - Watching videos in short and long formats.

Sending ephemeral messages privately and publishing timely, in-the-moment content for all of your followers to view for up to 24 hours. - Snapchat, Instagram Stories, Facebook Stories, LinkedIn Stories

Asking and answering questions, networking, forming communities around niche- and interest-based topics. - Reddit, Quora

Researching and purchasing products from brands directly through social media platforms. - Pinterest Product Pins, Facebook Shops, Instagram Shops, TikTok, Shopify, Douyin, Taobao

Broadcasting live video to many viewers. Live video streams can range from one person showing themselves and what they’re doing on their screen to professionally organized panels with multiple speakers. - Twitch, YouTube, Instagram Live Rooms, Facebook Live, TikTok

Connecting with professionals in your industry or potential clients. - LinkedIn, Twitter

Creating communities, with the possibility of requiring registration or other screening measures for new members. - Discourse, Slack, Facebook Groups

Searching for information and finding inspiration for anything from cooking to travel to decorating to shopping and more. - Pinterest, YouTube, Instagram, blogs

https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/issue/view/492

References

D.M.Boyd and N.B.Ellison, Social Network Sites: Definition, History and Scholarship (2008)

S.Edosomwan, et.al., The History of Social Media and its Impact on Business (2011)

Sai Srinivas Vemulakonda, Emergence and Growth of Social Media (2018)

D.Wilding, et.al., The Impact of Digital Platforms on News and Journalistic Content (2018)

R.V.Kozinets, A History of Social Media (2019)

Social Media Trends 2022